Up the Rio Negro: Manaus to Colombia by Boat

Amazonian shamans; one week on a boat; and the village at the end of the World…

Up the Solimões:

After several hazy weeks in the sultry Amazonian metropolis of Manaus, yet another tropical night found me enjoying beer, cigarettes, and the company of a flame from the Brazilian coast. We were at a well-known bar outside the iconic Theater of Amazonia. As I watched two European tourists walk through the plaza with a pair of sculpted, tattooed manuara women with waist-length black hair, a stranger approached our table. Within seconds, he bummed a cigarette and summoned the waitress to fetch him a glass so he could share the large bottle of beer in the middle of the table. Typical of the locals in Manaus, his demeanor was ragtag and happy-go-lucky: long hair, punk-rock attire, and the typical face of a caboclo, an Amazonian inhabitant of mixed Portuguese and indigenous ancestry. He wore a weathered grin, and his countenance reminded me of Keith Richards.

He asked me what I was doing in the middle of the jungle, and I replied that I was going to volunteer with an NGO in traditional communities in the neighboring Amazonian region of Rondônia. He launched into a racist tirade about the backwardness of os indios. The fact that his own ancestry was indigenous did not deter him.

“Kid, my grandparents were Indians living in the forest, so I for one can really tell you how backward, lazy, and hopeless they are,” he bemoaned.

Then he turned a jealous eye to the European backpackers and their local companions.

“See those girls over there? Their grandparents were Indians too. I would love to screw them, but it’ll never happen—Why?—Because I look like an Indian instead of a gringo. See, they’re the ones who are racist—not me! By the way,” he ranted on, “if you want to see real indigenous communities, Rondônia é uma merda (Rondonia is a piece of shit). A couple of generations ago, German-descended settlers from Central-West Brazil, white and blue-eyed just like yourself, went to Rondônia and cut down all the forest to create cattle ranches. Now, there are no more Indians and no more jungle in Rondônia.”

I asked him about Roraima, the Amazon state north of Manaus and bordering Venezuela.

“E outra merda!! (It’s another piece of shit!),” he sneered. “If you really want to see the true Amazonia and the untamed Indians, you have to travel six days by boat to the last city before Colombia, São Gabriel da Cachoeira.” He might have been a drunken hustler, but by the end of the night, he had me sold.

**

The next morning I headed down to the Port of Manaus to inquire about boats leaving for São Gabriel. The port reminded me of a Mississippi River town from Huck Finn: dozens of brightly colored, double-decked boats lined up and the bank bustling with drunks, vendors, fishermen, and pickpockets. The ships departed for all corners of the oceanic Amazon: One for the tri-border of Brazil, Peru, and Colombia; one to the south to the border with Bolivia; another to the Atlantic port of Pará, where the Caribbean and Amazon collide into each other. With a few connections and ample patience, a traveler could take boats all the way to the continent’s obscure, swampy corner of Suriname and the Guyanas. Thousands of crates a day of açai, lumber, soy, fish, Brazil nuts, and smuggled Colombian drugs flowed through this port.

As luck would have it, there was a ship leaving the next day that would arrive about six days hence in São Gabriel. I rose at the crack of dawn the following day to pack and buy six days’ worth of bottled water, dried fruit, and ‘rotten cakes’ (a delicious and cheap Amazonian snack made with fermented tapioca and dried fruit). I made sure to board the boat two hours early to find a good place for the hammock, far from the engine room and the horribly dirty latrines. The boats were always packed far past a safe capacity, and I had learned the hard way that dilly-dallying in arranging your hammock resulted in sleepless nights lying on the floor somebody else’s hammock.

The boat ride was six easy days of fresh air and enchanting glimpses into the vast jungle of the tea-colored Rio Negro. After the third day on the river, civilization was left hundreds of miles downstream, and I was in pristine, primary forest. Here was the Amazon in all her grandeur and majesty. The air was delicious to breathe and lulled me into deep and restorative sleep each night. I awakened to sunrises over the river to enjoy breakfasts of fresh fruit and Brazilian cafezinho with the other passengers. We stopped in small jungle villages for an hour or so each day for the crew to unload or bring cargo on board. I passed the hours reading, strumming a guitar, and chatting with other travelers: soldiers heading to the bases Brazil’s Amazonian frontier bases; indigenous people returning to their communities after studying or working in Manaus; Colombians and Peruvians who spoke porteñol and had crossed the border to find better economic opportunity Brazil. My buddy, a Carioca who worked for a state-sponsored research institute, was lucky enough to have one of the few cabins on board, and he quickly met a woman to keep him company within it. When she disembarked in her village a couple of days later, he found another cabin mate that same day.

**

The port of Sao Gabriel came into view on the sixth morning of the voyage. We were eating breakfast, and all cheered for the completion of a smooth journey. The toponym São Gabriel da Cachoeira refers to the treacherous whitewater rapids that form at this point in the Rio Negro. The rapids prevent large ships from going further upstream; only small, nimble boats piloted by seasoned captains can pass through and continue to Colombia. The terrain in this part of the Amazon is mountainous, and there is a famous vista of the “Sleeping Beauty,” a section of mountains that resembles the profile of a reclined woman. During the dry season, the river recedes hundreds of yards and forms a gorgeous sandy beach, lined by the jungle and the mountains. The Upper Rio Negro, often referred to as the Heart of the Amazon, is home to many indigenous cultures, and the city of São Gabriel recognizes more than 25 official languages.

I found a hotel with my researcher friends from Manaus. The place was simple, patronized mainly by researchers coming to study indigenous communities from across Brazil. My friends planned to fly to the Yanomami territory to the North near the Venezuelan border the following day. There they would conduct research on the water and soil high up in the mountain range with the highest peak in Brazil, O Pico da Neblina. Knowing that there would be one extra seat in the small prop plane, they invited me to join them in Macuratá, the huge national park where the Yanomami reside.

I spent the rest of the morning sending emails in the town’s sole location with internet, a dilapidated computer café. A girl walked in and sat down next to me. She exemplified the beauty of the women from this region I found so hypnotizing: long, luscious black hair, fierce-looking eyes, and a body that looked the way an electric guitar sounds. I spotted a tattoo covering her entire outer thigh, working its way up into her tiny shorts. As she exited the café, I walked out with her. She gave me a curious look and we exchanged smiles. I asked her if she knew the town well.

“No,” she said with a grin. “Just visiting from Manaus with my aunt. What in the world are you doing here?”

“I arrived in Manaus from the US a few weeks ago, and now I’m trying to get permission to visit a protected indigenous community.”

We joked with each other for a few minutes, and she asked me to meet up with her before she left town the following day.

“Come say hi later,” she invited. “We have nothing to do here at the end of the world.” She winked and then turned to cross the street.

I ran into her a few hours later in the plaza, and this time she was dressed up and wearing make-up. We walked around the town for an hour and then made love in her sweltering hot hotel room until her bed was a swimming pool of sweat. Euphoric and laughing, I lost track of how many rounds we went or how many hours passed. The front desk staff eventually banged on our door, signaling it was time to take a break. We walked out to the street hand in hand, descending the hotel’s concrete stairs into the late afternoon sunshine. I bought us some bowls of cold acai, and we sat and enjoyed the afterglow. Ah, Brazil—this is how you stole my heart long ago. Your magic reaches into the depths of the Amazon.

When I returned to Sao Gabriel from the Yanomami reservation the following evening, my beautiful friend had departed. The front desk receptionist informed me, looking rather bemused, that my namorada had left a gift for me. It was a book by Paulo Coelho inscribed with a note and signed with a lipstick print. I caught a trace of her perfume.

Adventures with a Baniwa Medicine Man:

I made friends in the bars that dotted the river in São Gabriel, and a local guy invited me to crash at his family’s house. Joel, my new host, was the unofficial mayor of São Gabriel. He knew the entire populace of the city and possessed a vast reserve of knowledge of his region and its many cultures. Joel had tramped extensively through the Rio Negro, even sojourning among guerrilla in Colombia and among his kin in an isolated Tukano village for several years. A brilliant artisan, he produced intricate and exquisite jewelry—made with metal wire, seeds, feathers, and string—that he sold on his travels. Joel’s mother was a Tukano Indian, and his father, now living in a Colombian mining camp, was a traveler of Romani descent from the desert interior of Ceará. His left forearm bore a psychedelic portrait of Frank Sinatra and his right an interstellar landscape scene; when he was younger, he had been designated as the experimental guinea pig at his older brother’s tattoo studio in Manaus.

Apart from being the most indigenous city in Brazil, São Gabriel gained notoriety as a hideout for outlaws. As we walked down the florid streets of his neighborhood, Joel recounted how a Rio de Janeiro drug kingpin once briefly absconded there. The Rio police closed in on him in his favela, so he sought asylum with his business partners in the FARC. The drug lord, en route to the guerrilla jungle camps across the border, hid out in São Gabriel for a spell. His capture was executed through a joint effort of the Colombian and Brazilian militaries and brought national media attention to this otherwise sleepy jungle town.

When we passed the largest bar on the river, Joel explained it was common knowledge that the Colombian owner had been a trafficker in Medellín. Looking to get out of the business once and for all, he opened a bar in this remote corner of the Amazon and married a local indigenous woman. We then walked by a massive store selling electronics, agricultural equipment, and motorboats. The owner had arrived dirt poor from Brazil’s northeastern desert, but within a few years had become one of the wealthiest men in the city. How did he get so rich so quickly? Smuggling illegal gold from the Yanomami territories, Joel affirmed. In fact, the numerous jewelers outside the central market made a fortune transforming illegal gold into simple bracelets or necklaces that could be transported relatively risk-free. We passed a solitary mansion, the occupant of which had been a strange, old man who spoke little Portuguese. When the man died from old age, the residents of São Gabriel found his house full of swastika regalia and WWII-era pistols. It was later confirmed that he was a fugitive Nazi.

Joel explained how to recognize the tribal origins of a basket or piece of jewelry by its designs and patterns as we walked through the open-air market that was the beating heart of Sao Gabriel. He could immediately identify the ethnicity of any indigenous person we came across there. This man selling bags of dried ants was Tukano. They were the tallest and largest Indians of the region, the dominant tribe in pre-contact times. This curly-haired woman selling fish was Baré, a tribe who had long ago intermarried with miners and rubber-tappers coming from northeast Brazil and often had Afro-Brazilian features. This man selling tucupi, a fermented tapioca liquid used as a seasoning, was Dessano, a related tribe to the Tukano. There was a Yanomami, who had probably traveled the better part of a week to arrive here from Maturacá or farther north. Most of the time, the reason to visit Sao Gabriel was to buy things—tools, medicine, groceries—or to sell their crops or handicrafts in the market. Other times, the motivation was to enjoy a few nights of booze and debauchery in the town’s gritty casas de festa, dance halls on the river with sandy floors and bands playing pulsing and raucous Manaus-style booty beats.

There was one ethnicity I kept seeing in the people at the market who looked quite different from the other indigenous people. They were tiny in stature, with dark complexions and distinctive facial features, matted hair, stocky bodies, and without the Asiatic features of most indigenous Americans. In fact, their appearance reminded me of Melanesians or South Indians. Sadly, it was obvious that these people were the most desperate of all; the ones I encountered in the market were often drunk, unwashed, and sickly. Joel informed me that these people were collectively called Maku, nomadic pigmies who followed yearlong migration paths through the jungle. They followed the cycles of wild fruits such as cupuaçu, tucumã, and wild açaí, and would fish for crabs and small fish in inland ponds. They traveled in familial groups of six to fifteen people, sleeping wherever they happened to stop to rest. Members of the group rotated as lookouts—after all, the jungle is full of dangers.

The indigenous mythological traditions of the Alto Rio Negro state that the Maku are the “grandfathers” of the Amazon. A myth that exists across cultures in the Rio Negro is that a giant, cosmic Anaconda descended upon the river and deposited each tribe from his mouth in their respective land. According to this myth, the Maku were already there. Moreover, the Maku language is isolated from the other languages’ families of the Rio Negro; in other words, if Tukano, Dessano, and Coripaca were the Spanish, French, and German of the Rio Negro, Maku would be the Basque. Due to the alienness of their language, the other ethnicities pejoratively referred to Maku by a slur meaning “those without speech.” They had been practically unknown to the non-indigenous world until a few decades ago, as they used to flee into the forest immediately when they saw a branco or any non-Maku indigenous person.

I became most familiar with the Maku ethnicity known as the Dâw and visited their reservation across the river from São Gabriel. The Dâw history is the saddest of any ethnicity in the Amazon. In pre-contact times, the Tukano and Dessano enslaved them, and in post-contact times, the vices brought by the white man, namely hard alcohol, has driven them to the verge of extinction. Just twenty years ago, their survival seemed unlikely, and the last of them were dying in the gutters of São Gabriel from alcohol poisoning and exposure. The white man’s liquor is a scourge for nearly all the world’s indigenous populations, but the Dâw were especially devastated by its introduction. They could rarely afford even the cheapest cachaça available and would resort to drinking cleaning alcohol and cheap perfumes sold on the street. Markets in São Gabriel would place plastic bottles of cleaning alcohol on low-lying shelves below glass bottle cachaça. They often hired themselves out for an entire day of menial labor in exchange for a bottle of cheap, hard swill. Young children became alcoholics as they watched their parents waste away in drunken stupors on a daily basis.

An evangelical church from Manaus, which purchased land across the river from São Gabriel and donated it to the remaining Dâw in the nineties, saved their culture. A minister from this church gathered the last of the Dâw off the streets of São Gabriel and organized them into an evangelical community. They were required to abandon their traditional beliefs and much of their culture, but they also gave up alcohol and glue sniffing. To the astonishment of all in São Gabriel, they began to make a comeback, albeit a precarious one. When I was in São Gabriel in 2015, I was told there were about 100 recognized Dâw, but with only a small handful of full-blooded elders. Their language is taught and spoken in their community, but their traditional culture and lifestyle have been mostly erased. Luckily, the related Maku groups, although marginalized and beset by miserable poverty, are not in danger of extinction.

**

I had been staying with Joel’s family for a couple of weeks, and one morning we went out to buy fresh fish and herbs in the market. A small Indian with elf-like features and broken Portuguese came over to greet us. Although his face was creased with age, his mirthful eyes and smile belied a spirit of youthful joviality. Joel introduced him as Seu Luis (Mr. Luis) and the leader of a protected community of Baniwa Indians. He was with his young grandchildren, and I offered them some doce de leite. They looked at each other with an expression like they had just won the lottery. Seu Luis and I exchanged a couple of jokes about our mutually funny Portuguese, and he encouraged me to visit him before I left the region.

Joel explained that Seu Luis was a pajé, an Amazonian medicine man. In fact, he was one of the most respected and renowned pajés in the Rio Negro. He had learned how to cure, bless, and practice divinization in Baniwa territory further north on one of the hundreds of tributaries of the Rio Negro. As a youth, Seu Luis spent weeks alone in the wilderness, fasting, praying, and listening to the jungle. By use of song, prayer, and herbal medicine, Seu Luis treated ailments of the body and spirit. Local mothers would bring their infants to Seu Luis to “close baby’s body to evil.” Joel’s brother, a tattoo artist, had contracted severe kidney stones a couple of years prior, and the doctors in Manaus told him that immediate surgery was necessary. Instead, he opted to return to São Gabriel to consult with Seu Luis, who used plant-based concoctions to break up the kidney stones which rendered surgery unnecessary.

Luis was a remarkable frontiersman, intimately familiar with the Rio Negro and its flora and fauna. He knew how to procure medicine, psychotropics, and food from its seemingly inhospitable depths. When Joel and I went to visit him at his maloca—a huge building of bamboo, timber, and palm fronds constructed without nails—his wife informed me that Luis and his grandsons had been away for several days in a nearly inaccessible region. They were trying to collect a plant fiber that was ideal for basket weaving. A renaissance man, Luis spoke Portuguese, Baniwa, and several other indigenous languages (his wife was from another ethnicity of the Rio Negro), and he was a masterful musician. Accompanied by other Baniwa instrumentalists and vocalists, he would play strange and beautiful melodies on a massive didgeridoo-like wooden flute.

Seu Luis was unfailingly comedic, and his gift for storytelling, even in limited Portuguese, was extraordinary. One evening, Joel and I walked into his maloca to see a quartered monkey carcass roasting over an open fire. I asked Luis if he had ever managed to tame a monkey as a pet, to which he shook his head and chuckled: “Johnny, I did have one monkey as a pet, right here in this very maloca. What a naughty little bastard he was! Every night when the young girls were trying to sleep, the monkey would crawl into their hammocks and try to touch them…in the place where they pee! Safado! (Horny devil!) You understand now why I never want another pet monkey?”

The flesh around my fingernails had become infected with tiny parasitic maggots, a disgusting yet common nuisance in the Amazon. Joel and Luis removed them for me with a sewing needle, taking pains to avoid rupturing the vermin’s body, a folly that would have released its eggs. Chuckling, he carefully lifted a maggot the size of a grain of rice out of my finger and pointed out another one on my toe. Luis exclaimed, “Joel, your white friend here reminds me very much of one of the stray dogs in our village.”

One night, Joel and I bought beef, chorizo, rice, and beans in São Gabriel and went to cook dinner for Luis and his family. Joel had worked as a sushiman for years in Manaus and was an excellent cook. He knew the origins and the uses of all of the bizarre fish, insects, herbs, and bottled concoctions available in the market, including which purveyors had the freshest fish, the tastiest açaí, or even semi-legal bush meat such as paca, a large rodent that is a coveted delicacy in indigenous communities. He explained the best seasons to buy specific types of açaí and the uses of the astonishing variety of local chili peppers.

“See this chili here? It is one of the strongest in the region,” he would explain. “They say that an isolated tribe of Yanomami used to gather this chili only when they were to consume human flesh.”

Not only could Joel create delicacies from the exotic jungle ingredients of the Rio Negro, but he could also perform culinary magic without the basics of a simple kitchen. In Luis’s maloca, using only a campfire, beat-up aluminum pots, collected rainwater, and a tiny knife, Joel whipped up a feast of rice and beans with chorizo and steak seasoned from Seu Luis’ herb garden. For dessert, Joel surprised us with açai wine, the regional term for freshly squeezed and bagged açai pulp. Luis kept us laughing over dinner with stories of shenanigans that came to pass in the village: “Johnny, we used to have a problem with a thief here in the community. Every other week or so he would sneak into my maloca and steal bags of rice, beans, fuel…” Then furrowing his brow as if to trying to remember more details, he exclaimed, “And money! That one thief really liked to steal money in particular.”

Arising one morning from my hammock in Luis’ Maloca, I was surprised when Luis asked Joel and me over the morning’s coffee what we had dreamed about. I vaguely recalled that I had had a bizarre dream about a monkey running around the maloca. I mumbled something about it to Luis, to which his face lit up with excitement as if he had been hoping I would say exactly that. Joel also mentioned something about a similar dream.

“Johnny, that is great news! That mischievous monkey was in my dream first, and then he migrated over to Joel’s dream and finally to your own. It’s a good sign.”

I looked at Joel in disbelief, but he seemed to be unfazed and in agreement.

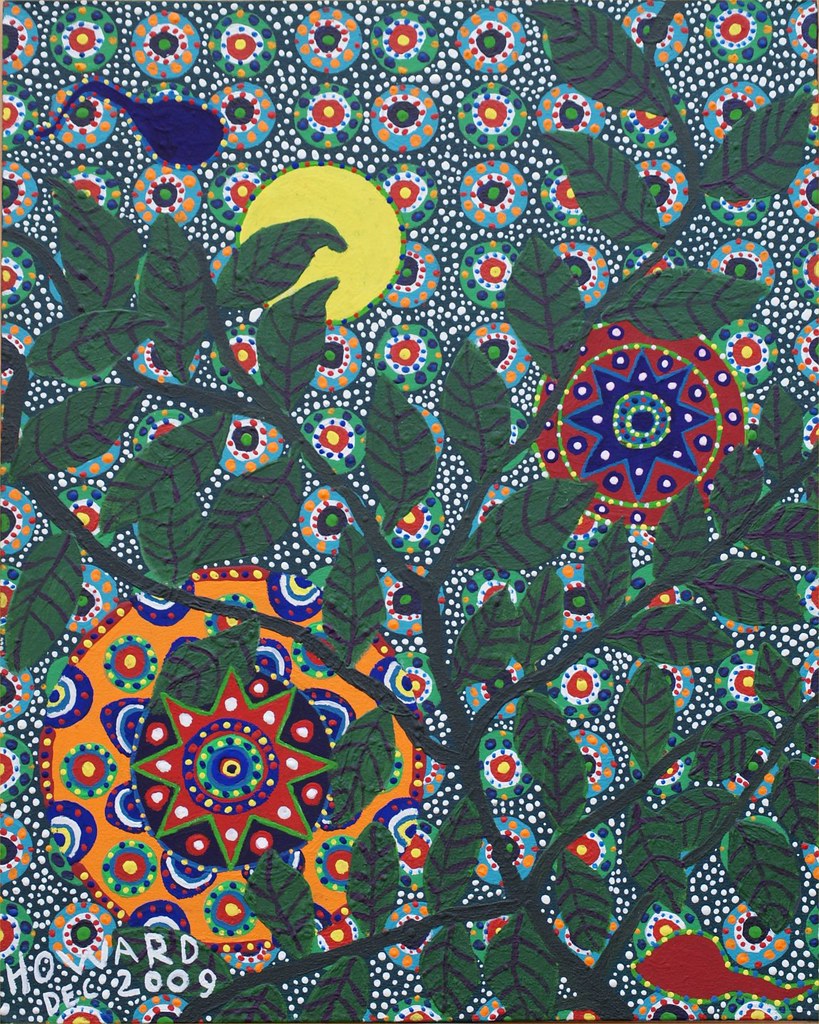

The day before my boat back to Manaus was scheduled to depart, I dropped by Seu Luis’s maloca to say goodbye. When I arrived, he was seated with his hands full of brownish plant fiber, effortlessly weaving baskets. Luis had created a black dye from charcoal and a red dye from a berry, and the baskets bore complex, geometric designs of traditional Baniwa art. I asked Luis if I could purchase some of the completed ones, and he was delighted to sell them. Remembering that Luis was renowned as a blesser, I asked him if he would bless the baskets as well. He obliged me and sat down on a wooden bench in the middle of the maloca with the baskets in his hands, then began to chant softly in Baniwa and entered into a trance, gently rocking and humming over the baskets for about half an hour. I became slightly embarrassed that I had asked for so much of his time. Sensing my discomfort, his grandson assured me that Luis would be done shortly.

A few minutes later, Luis stopped rocking, stood up, and placed the baskets where he had been sitting. Still humming under his breath, he walked over to me and asked me to sit down. He then placed his hand on my head and continued singing, pursed his lips, and blew air around my face, neck, and into my t-shirt. Luis finished the blessing, and, with warm, smiling eyes, told me that he had summoned protection and good luck to follow me. I felt light in my chest, an emotion of relief and reassurance. It was mid-morning and walking out of the maloca, I was struck by how gorgeous the golden, tropical sunlight was. The world appeared fresh and beautiful as I left and walked towards the solitary dirt road back to São Gabriel. The feeling of rejuvenation and freshness stayed with me for months afterward and carried me through the New England winter that awaited my return to the U.S.